The BBC examines women’s history with cats amid 2024 US election discussions regarding “childless cat ladies”.

Cats have characterized feminine sexuality in the Western male gaze more than any other animal. Female “sex kittens” “purr” seductively and have “feline” beautiful looks. The desexualized “cat lady” stereotype contrasts with the “sexy cat” cliche. Recently, Donald Trump’s running mate JD Vance’s 2021 remarks revived the “cat lady” myth. Where did it start?

A spinster, or lesbian, is the cat lady cliché. She is usually a cardigan-wearing, bespectacled loner with at least one cat. Alice Maddicott, author of Cat Women: An Exploration of Feline Friendships and Lingering Superstitions, tells the BBC that cats and women have always had a sex divide.

Being called a ‘cat woman’ desexualizes you, yet it may also mean promiscuity and passion – Alice Maddicott

Maddicott claims Chaucer’s Wife of Bath was termed a cat “in order to insult her and suggest she was promiscuous – she went out ‘a-caterwauling'”. So, “being a ‘cat lady’ desexualises you, but that cat can also be used as an insult referring to promiscuity and lust.” Consider the name “cougar” for women who date younger guys.

Woman-cat relationships are older and more prevalent. A half-cat, half-human goddess, Bastet, was the goddess of domesticity, fertility, and childbirth in ancient Egypt, where cats were tamed approximately 10,000 years ago. She safeguarded the house from bad spirits and illnesses and guided and helped the deceased in the afterlife, like most Egyptian deities. In Greco-Roman periods, Bastet was seen as Artemis (Greece) and Diana (Rome), with her cat connection much diminished. Artemis and Diana appeared as humans, with Diana becoming a cat in Ovid’s Metamorphoses when the Roman gods fled to Egypt. In Norse mythology, Freyja, the goddess of fertility, love, and luck, drove a chariot driven by two male cats. Li Shou, the cat goddess, controlled pests and fertility in ancient China. When did the relationship between women and cats, especially in the West, become bad and controversial?

The cat-woman bond begins

Christianity seems to be the solution. “Effectively women and cats in unison were associated with pre-Christian goddesses,” Maddicott adds, “the church would have frowned upon and [could] be the root of some of the suspicion that later exploded with the witch trials.” (Witch trials were sessions against alleged witches, often women. Convicted offenders were executed). Katharine M. Rogers argues in The Cat and the Human Imagination that the Roman Catholic Church called free-roaming unmarried women “cats on the prowl” in the Middle Ages. Later, all non-Christian deities were labeled bad and cats Satan’s henchmen to exterminate non-Christian faiths in Europe. Religious propaganda portrayed women, cats, or both as bad.

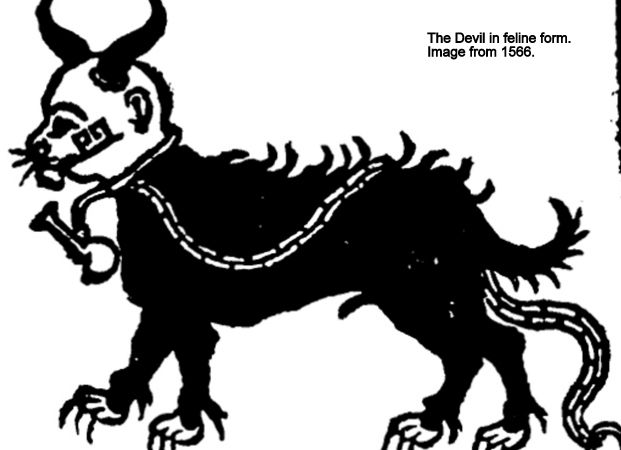

Pope Gregory’s 1233 Vox in Rama decretal described Europe’s “problem” with non-Christian faiths, accusing them of practicing demonic cults and detailing their rites. Donald W Engels’ Classical Cats: The Rise and Fall of the Sacred Cat states that this papal order granted “divine sanction for the extermination of the cat, especially black ones, and the extermination of their female owners”. In 1566, England’s first witch trial killed Agnes Waterhouse, who admitted that her familiar was a cat called Sathan (Satan), which eventually became a toad. The 63-year-old was executed, cementing the cat-woman-witch association in the US until the Salem witch trials.

“[Cats] are independent and often intelligent – things that in the past if people were trying to control women they would not want them to be,” he explains. This disrupted the Christian hierarchical order of life on Earth, where man was at the top. Katharine M. Rogers expounds: “Cats easily symbolize what males have long and bitterly grumbled about women: they don’t obey and love enough. Men who can’t manage women want to compare them to animals.” Cats appeared in early 20th-century US anti-suffrage cartoons to mock and denigrate the women’s movement.

Professor Fiona Probyn-Rapsey, a feminist postcolonial animal studies professor at the University of Wollongong, tells the BBC that cats and women are part of a larger human-animal connection. “The ideas that we have about animals feed into ideas about gender,” adds. “We routinely use animal tropes to talk about gender, and to police gendered behaviours (“bitch”, “hen-pecked”, “stud”, “cougar”) as well as [race and] racism, which is always making use of animal tropes to dehumanise and deny the humanity of others.”

Popular culture cat women

After being labeled spinsters and old maids for draining family’ wealth, unmarried women with cats were doubly condemned. By Victorian times, this relationship was cultural. The Dundee Courier said in 1880 that “the old maid would not be typical of her class without the cat,” and that “one cannot exist without the other.”

The single-woman-plus-cat cliché remained throughout the 20th century, maybe peaking in 1976 with Grey Gardens. Its subjects were Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis relatives Edith Bouvier Beale “Little Edie” and her mother Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale “Big Edie” at their 14-bedroom East Hampton, NY house, Grey Gardens. Overrun with tens of cats, food tins and trash dotted the house’s floors and grounds were overgrown. The documentary warned about what happens to a woman without a man: Big Edie got divorced and Little Edie never married.

“The [cat lady stereotype] helps label women who are seen as unacceptable in terms of patriarchal societal expectations,” Maddicot adds. “Society stereotypes older, unmarried, childless cat ladies as failures. If you don’t do what’s required, you might wind yourself alone and, if you have cats, in filth and desexualization like Grey Gardens.”

Grey Gardens shaped cat women on television for decades. Pfeiffer and Berry’s Catwoman roles featured cat ladies (Pfeiffer was one in Batman Returns (1992) and Berry is mentored by one in Catwoman (2004)); Mrs. Deagle from Gremlins (1984); Eleanor Abernathy from The Simpsons (first appearance 1988); and Robert De Niro on SNL (2004). The LEGO Movie (2014) included Mrs. Scratchen-Post, a 20-cat owner. Both the book and film versions of The Clockwork Orange, Professor Pringle’s Aunt Jane in PG Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster series, and Miss Caroline Percehouse in Agatha Christie’s The Sittaford Mystery feature cat ladies.

Recently, popular culture’s dread and cautionary story about cats and women has become comedic relief. The newly unmarried Lorelai phones her daughter Rory after one cat, then two, arrives on her porch in Gilmore Girls (2000–07): “They know. Cats know… I’m alone. Probably need to start collecting newspapers and magazines, locate a blue bathrobe, and remove my front teeth.” After being single, Rebecca jokes to her pals in a musical song about becoming a cat lady in Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (2015-19). Thus, the cat woman stereotype is mostly a cliché.

Traditional cat-woman stereotypes are losing favor. Women have more freedom and power to life outside the historical “norms”: many are opting to be single and child-free; they have more job influence; and feminists finally use the name “spinster” again. Many cat owners, like Taylor Swift, openly utilize “cat lady” on social media.

“There are so many wonderful examples of women-and-cat friendships being what they actually are, a positive nice normal pet relationship, rather than the stereotype,” he adds. JD Vance’s “childless cat lady” statements referenced Vice-President Kamala Harris, who is the stepmother of two. She does not own a cat, but the historical relevance and implication remain. Perhaps a woman or anyone of any gender who chooses to be a “cat lady” (whether they have one or not) should do it on their own.