On August 2, 1939, Albert Einstein wrote to Franklin D. Roosevelt. His letter led to the Manhattan Project, one of history’s most deadly innovations.

Had a two-page letter from 2 August 1939 never been written, the 2023 blockbuster film Oppenheimer’s harrowing description of the lethal harnessing of atomic power might have been science fiction.

Albert Einstein wrote to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Recent work in nuclear physics made it probable that uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy,” to which he signed by hand. He suggests using this energy “for the construction of extremely powerful bombs”.

The letter sparked the $2 billion “Manhattan Project” to outpace Germany in atomic weapons development by expressing skepticism at Germany’s determination to restrict uranium sales in occupied Czechoslovakia. Oppenheimer’s three-year project brought the US into the nuclear age and produced the atomic bomb.

Einstein’s carefully phrased letter will be auctioned at Christie’s New York on September 10, 2024, perhaps for over $4m. A shorter version, auctioned by Christie’s, and a more extensive one, hand-delivered to the White House and now at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in New York, were written.

“In so many ways, this letter marks a key inflection point in the history of science, technology and humanity,” suggests Christie’s senior Americana, books, and manuscripts specialist Peter Klarnet to the BBC. “This is really the first time that the United States government becomes directly financially involved in major scientific research,” he says. “The letter set the ball rolling to allow the United States to take full advantage of the technological transformations that were taking place.“

Dr. Bryn Willcock, Swansea University’s Department of Politics, Philosophy, and International Relations programme director and American and Nuclear History lecturer and researcher, agrees. “Most historical accounts of the origins of the bomb begin with a discussion of the letter,” he says. “The letter’s contents were key to getting direct action from President Roosevelt,” he adds, noting “the Atomic Heritage Foundation goes as far as to describe the letter… as ‘vital’ in pushing Roosevelt into undertaking atomic research.”

The award-winning film Oppenheimer, which is based on the Manhattan Project, includes the letter in a sequence between Oppenheimer and physicist Ernest Lawrence, which should boost auction interest. “This [letter] is something that has been part of the popular culture from 1945 onwards, so it already has a firm place, but I think the Oppenheimer movie brought it now to a new generation,” he adds.

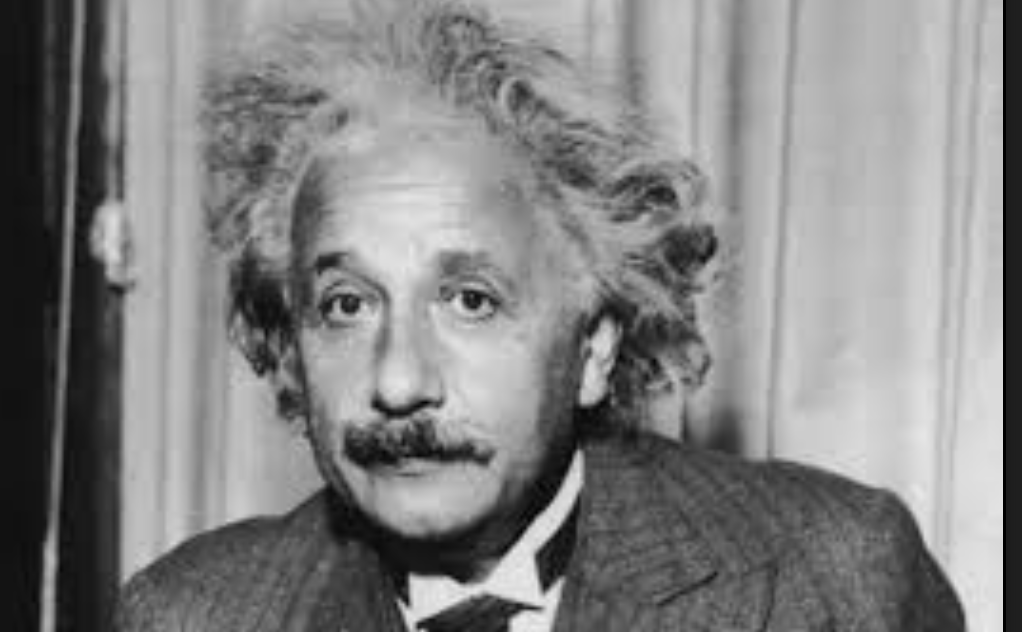

Klarnet calls Einstein “a mythical character” in pop culture. He has that quality in Oppenheimer, lurking at the film’s perimeter like a cameo we anxiously expect, his identity revealed when his hat flies off and reveals that iconic shock of white hair.

Einstein distanced himself from the project and claimed his role in atomic energy release was “quite indirect”

The video overstates Einstein’s role in creating an atomic bomb, even while his equation E = mc2 explained nuclear reactions and allowed its nefarious use. Klarnet dismisses the concluding scene’s dramatic interaction between Oppenheimer and Einstein (“When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world…”) as “nonsense”.

He claims Einstein “did not have the security clearance for that” due to his left-leaning ideas and German origin. The pacifist avoided the project and said his role in atomic energy release was “quite indirect”.

Einstein’s former student Leo Szilard started it. Szilard kept the letter with his pencilled “Original not sent!” until his 1964 death. Nazism had driven Jews like Einstein and Szilard to the US, and they knew Germany’s menace better than anybody.

Szilard created the letter but persisted in getting Einstein to write and sign it. Klarnet calls Einstein “the personification of modern science” after receiving the 1921 Nobel Prize. “He has unique influence. In the months leading up to this, others tried to warn Roosevelt, but suddenly you’re walking in with a letter from Albert Einstein telling you to do this, which makes an impression.”

Security-cleared witnesses wore goggles as “the gadget” prototype was detonated in a New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945. Triumph and apprehension followed. President Harry S. Truman wrote in his diary: “we have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world”.

Germany had surrendered, but not Japan, and striking Hiroshima and Nagasaki with horrifying and unparalleled strength was supposed to finish the war. Szilard petitioned the authorities a day after the bomb testing to encourage Japan to surrender before taking such harsh measures, but it was not received.

Hiroshima received the “Little Boy” bomb on August 6. “Fat Man” exploded in Nagasaki on August 9. Many more died years later from radioactive after effects than the estimated 200,000 dead or injured. The only direct use of nuclear weapons in conflict is these.

Who knows if the Manhattan Project would have existed without Einstein’s letter. Willcock says Britain was “trying hard to push America into supporting greater research” and that the British-led MAUD Report (1941) on nuclear weapons feasibility was “crucial to pushing American research development”. Einstein’s letter merely sped things up. According to Willcock, a delay “would of course have likely meant that the bomb would not be ready for use by the summer of 1945.”

Einstein deeply regretted his 1939 letter’s violence and confusion. He co-founded the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists in 1946 to warn of nuclear war and promote peace. In 1947, Einstein wrote in Newsweek, “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing for the bomb.” Despite technological advancement, Germany lacks nuclear weapons.

Einstein spent his life for nuclear disarmament. He called the Roosevelt letter his “one great mistake in my life” in 1954.

The atomic bomb changed combat and started an East-West arms race that still shapes international relations. With nine nations having nuclear weapons, that letter explains much of our danger. “The issue remains pertinent. Klarnet calls it humanity’s shadow. “This letter is a reminder of where our modern world comes from and a stark reminder of how we got here.”

Posthumously, the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, an emotional resolution against nuclear war written by philosopher Bertrand Russell and endorsed by Einstein a week before his death in July 1955, used Roosevelt’s name. “We appeal, as human beings, to human beings,” reads part. Remember your humanity and ignore the rest. If you do so, you can enter a new paradise; if not, you risk universal death.”